Same-Sex Advertising Adventures of Military Men

By Bruce H. Joffe

Attribute it, perhaps, to the Great Depression and/or the coattails of the Motion Picture Code (Hays Code) of 1930, whose “Particular Applications” specifically restricted references to “sex perversion” (i.e., homosexuality) … but advertisements of the 1930s were relatively nondescript and anemic—especially in terms of sexually ambiguous imagery and homoerotic double entendres.

It wasn’t until the nation began to crank up for war in the 1940s that a renaissance in same-sex subliminal seduction resolutely appeared on the pages of America’s mainstream media.

World War II brought men and women from around the globe together in close proximity. Gays, lesbians, and bisexual people could encounter others like themselves … though, of course, it wasn’t acceptable to express one’s sexuality openly.

Nonetheless, a number of advertisements from these war years featured soldiers in all-male environments either enjoying ribald and racy recreation or engaged in some sort of unseemly activity that, today, causes one’s eyebrows to arch in amazement.

The Cannon Towel Collection

Fieldcrest Cannon Corporation, for example, ran a series of six “True Towel Tales” ads between 1943 and 1944 in several general-interest magazines. Showing soldiers bathing in the field and frolicking in a variety of licentious settings, the sequences showcase men engaged in what looks more like bawdy Boy Scout adventures than a weary and worrisome war. This homoerotic campaign of playful, naked men may be the inspiration for more recent beefcake advertising such as that produced for Calvin Klein and Abercrombie & Fitch.

Lest these ads be misrepresented, let’s go on record here and now by noting that these charming vignettes about life in the armed forces were unequivocally patriotic and domestically informative. Readers were reminded of the reasons they might not be able to find Cannon towels in their hometown shops — because “our boys in the service need them more than we do, so there are fewer to go around” — and given tips on how to make their towels last longer and stay “durable for the duration.”

Cannon produced advertisements honoring various branches of military service: the Army, Air Force, Marines, Tank Corps, and Navy. Supposedly, the story told in each ad is based on the actual recollections of a specified serviceman.

Accompanied by an illustration as described by an Army medic, “Army Day—Crocodiles Keep Out!”, Cannon’s True Towel Tales No. 1 (1943), is attributed to a doctor in the medical corps. Did you ever have to put a net across your bathtub—and share it with a crocodile? These naked soldiers might be smiling and having fun in the water but, according to their captain, sometimes you have to do that for a “bath” in the South Pacific Islands! “You might not enjoy the bathing facilities of our boys in the service,” says Cannon, “but you’d heartily approve of their towels.”

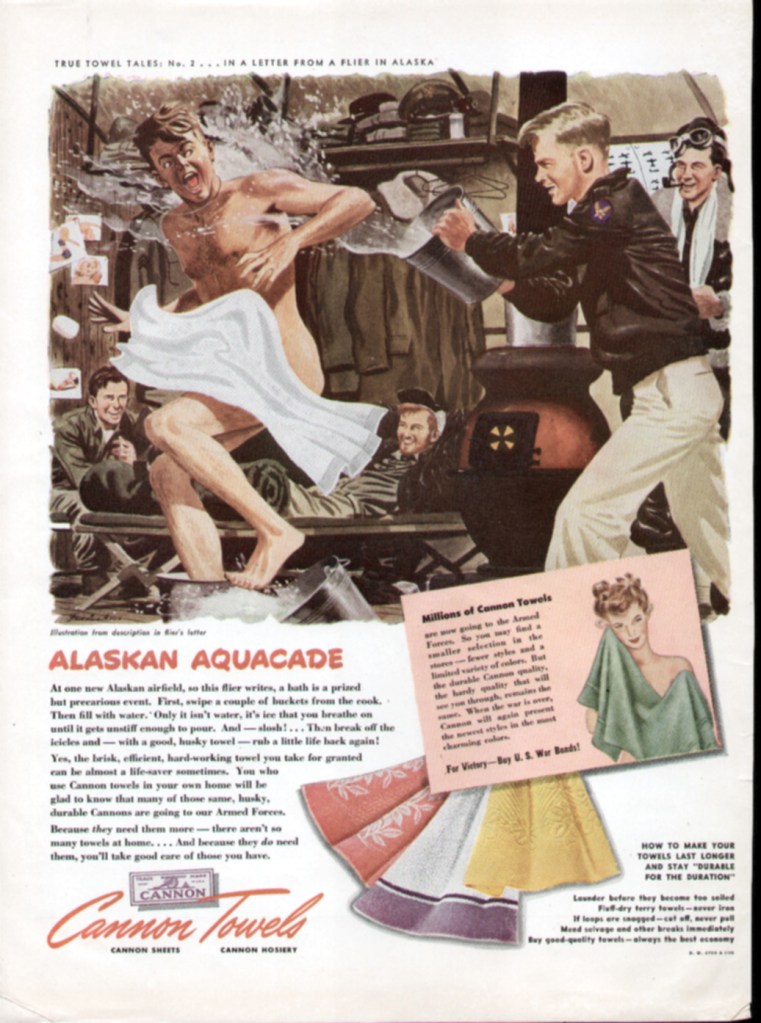

A half-naked airman is the subject of 1943’s “Alaskan Aquacade,” whose story was told in a letter from a flier. Chased around by a smiling buddy who throws water at him from a bucket, the surprised Air Force pilot is literally showered. A couple of grinning guys lounge nearby on the floor, under a rack of hanging uniforms. “At one new Alaskan airfield,” recounts the flier, “a bath is a prized but precarious event. First, swipe a couple of buckets from the cook. Then fill with water. Only it isn’t water, it’s ice that you breathe on until it gets unstiff enough to pour. And—slosh! … Then break off the icicles and — with a good, husky towel — rub a little life back again!” According to Cannon, the point is that “the brisk, hard-working towel you take for granted can be almost a life-saver sometimes.” Especially when dealing with an “agent” that’s too stiff for comfort!

Marines are featured in the third True Towels tale. In “…What? … No Bath Salts? …” (1943) even the illustration is based on a photograph supplied by the U.S. Marine Corps. Here the action takes place in the Solomon Islands, where “it’s either the Pacific with a shark to tickle his pinkies—or the water-tank.” When you’re “jungle-dirty” — as are these fighting men who take a break from battle to towel off and admire their handiwork — “the primitive water-tank’s a luxury,” claim our returned Marine heroes. Fortunately, where towels are concerned, the bath isn’t that primitive because the “brisk, efficient (Cannon) towels you take for granted are welcome equipment to our men in all the services.” Yep, welcome “equipment.” Towels!

Showing members of a U.S. Tank Corps in North Africa taking a nude swim and sunbath while a soldier poses playing Julius Caesar, Cannon’s 1944 True Towel Tales #4 is based on an experience told by a sergeant in the Tank Corps. Maybe the Roman bath was built for a conquering Caesar but in this advertisement it’s being used by “Joe Doughboy,” who’s enjoying a Roman holiday. The holiday includes lots of men doing their best to “camp it up.” When what ails you is the “Mediterranean heat and fight fatigue and pestering flies, a swim is welcome,” counsels Cannon. Welcome, too, of course, is the brisk rub-down with a good towel from the good-towel company.

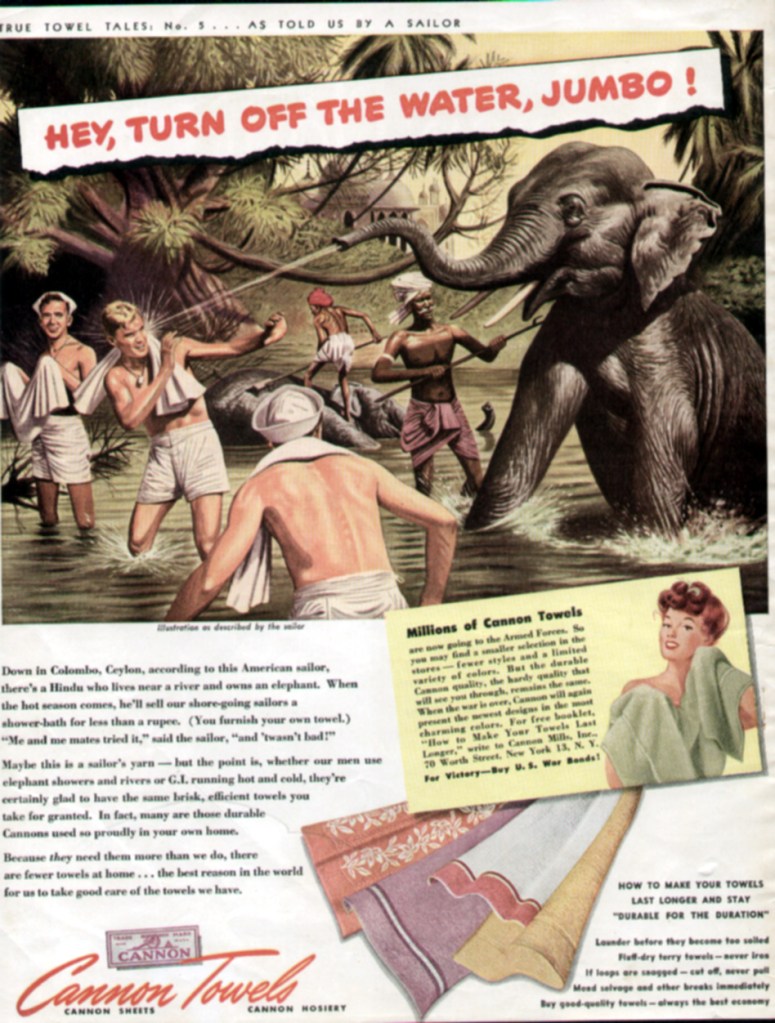

Now imagine yourself in boxer shorts, taking a bath with an elephant. That’s the scenario in “Hey, Turn Off the Water, Jumbo!” Cannon’s True Towel Tales No. 5. As told by a soldier, this 1944 ad shows Americans in Ceylon where an elephant hoses down the sailors with its trunk as natives wash the pachyderms. According to the story, “…there’s a Hindu who lives near a river and owns an elephant. When the hot season comes, he’ll send our shore-going sailors a shower-bath for less than a rupee.” Of course, one has to bring his own towel! Does the image of being hosed off by an elephant seem exciting … or appealing and tawdry? “Me and my mates tried it,” sez the Sailor, “and ‘twasn’t bad!” It’s different strokes for different folks as this ad goes to show that not everyone is comfortable with a jumbo hose, mate.

Fieldcrest Cannon’s final True Towels Tale (#6) was also published in 1944 and deals, again, with our Army men. This time they’re center sage in an abandoned canoe, taking a nude bath while the natives form an audience. As the villagers look on, a soldier playfully poses and vamps with a palm branch barely covering his body. Is this a bath … the “baths” … or a drag show? The canoe was full of rain water “and we were dirty,” explains the soldier. “The natives thought we were whacky—but whatta bath, brother, whatta bath!” Like the other ads in Cannon’s campaign, the men here seem to enjoy looking at each other’s nude bodies. This ad in particular seems to focus on a man pretending to be in drag, entertaining the men — some sitting between each other’s legs. One soldier looks on and whistles as, puzzled, the natives watch from afar.

Cannon’s strategy was an effective way to propagandize people to support the war effort, and provided some appealing eye-candy for women and the boys. Despite what could be construed as racist images of “natives” looking on as the military men bathe, the message is clear: Our GIs are having a good time, keeping clean, and out of harm’s way.

“The focus of these ads was on the value of Cannon towels to the soldiers, but the images were homo-erotic enough to allow for an alternate interpretation by a gay man,” says Edward H. Sewell (2005).

Bear in mind that on the battlefield, as in other gender-specific environments (i.e., same-sex boarding schools or jails), the absence of women could possibly have allowed for a more liberal and freer expression of man’s primal needs … and that, given the circumstances, society generally may have been more willing to waive its condescension or condemnation of such activities.

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell?

“The war years had witnessed a sudden and dramatic change in the appearance of men in Life magazine,” writes John Ibson (2002) in Picturing Men: A Century of Male Relationships in Everyday American Photography. “Men in various postures of intimacy had begun to appear in Life advertisements with remarkable frequency once the war was under way. In several issues just before the conflict, in 1940, the magazine had depicted no adult men alone together, without women; by 1943 and 1944, only one issue had no such male-to-male interactions in advertising.”

The potent mix of masculinity and patriotism symbolized by soldiers and sailors has, in its biochemistry, fundamental elements of seminal appeal. So, Cannon wasn’t the only company to employ homoerotic images in its advertising.

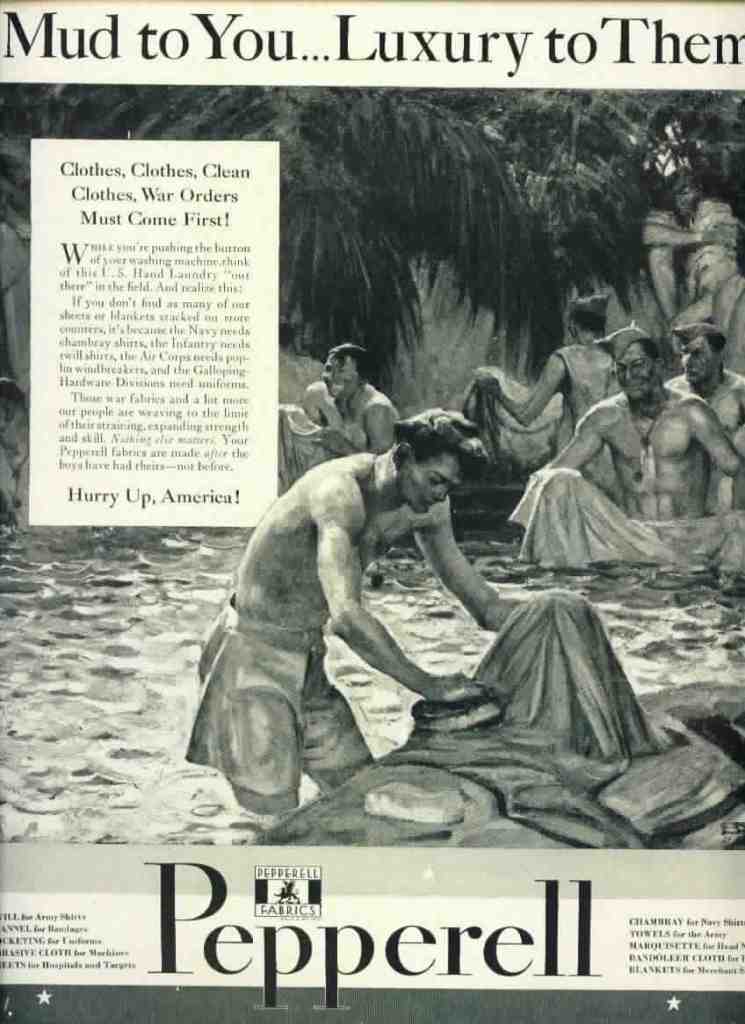

Nor was Cannon the only towel company to promote its products with advertisements featuring naked men engaged in activities, like doing laundry, associated with the gentler sex. A stunning illustration in a 1942 ad for the Pepperell Manufacturing Company of Boston shows the “U.S. Hand Laundry” corps in various stages of undress, cleaning their clothes in a river. With no washing machines or buttons to press, the muscular graphics undoubtedly drew admiration from men, as well as the attention of women.

Sacrificial Soldiers

Although a sense of free-spirited debauchery may be distilled from ads sponsored by Coca Cola, Pullman, Fisher (GM) Body Works, Armstrong Cork, Oldsmobile, Interwoven Socks, Listerine, International Harvester, and even Ma Bell, patriotism, sacrifice, and the welfare of our troops are all prioritized in these World War II ads … whatever else can be inferred or implied.

Perhaps no other ad so succinctly represents this primordial tug-of-war between protecting our boys and allowing the men their sexual latitude in such critical times as “The Kid in Upper 4” sponsored by the New Haven Railroad and published between 1942 and 1943. Immortalized by social historian Allan Berube (1990) in his definitive book on homosexuality in World War II, this ad has special significance: “Life in sex-segregated quarters created homosexual tensions as well as opportunities,” Berube contends. “A magazine advertisement illustrates how young recruits were placed ‘two in every lower berth’ on troop trains.” Presumably, the kid in upper 4 is depicted alone, worried, and wide awake because he is so young, so angelic, so blond. Poignant text about him leaving home and heading to war talks about what he left behind and what faces him ahead: “Next time you are on the train, remember the kid in Upper 4. If you have to stand enroute—it is so he may have a seat. If you have to wait for a seat in the diner—it is so he … and thousands like him … may have a meal they won’t forget in the days to come.”

What a tearjerker! A gay man’s eyes moist over this ad even today, thinking about what may befall this beautiful boy in the upper berth once he arrives “over there.”

Madcap Male-to-Male Interactions among Military Men

Madison Avenue’s woofish sketches of warfare revolved around sweat-drenched soldiers surrounded by other fighting men (and, at times, natives) who are either smiling and sneering or leering and jeering as they hand off erectile projectiles — artillery, missiles, guns, cannons or swords — to their comrades and/or combatants in arms.

The men here may not have been alone in the trenches, but their demeanor — sometimes saucy, other times threatening — and the winsome wording of the ad copy could coalesce to produce a sexually provocative response from some men in the advertising audience. Bombastic, iconoclastic … and homoerotic … are words that would agree with these sabers-rattling ads.

A 1943 full-color ad by Fisher, then a division of General Motors, is headlined “Body blow by Fisher.” Certainly the possibility exists for some double-entendre, especially as augmented by other ad copy here: “Take care of that equipment … make it last … make it do.” Beneath a blazing sky, this full-color advertisement shows a number of shirtless soldiers blowing off rigid cannons being both loaded and discharged.

That same year (1943), the National Dairy Products Corporation and Affiliated Companies issued its own call to arms with a smiling, jungle-based soldier “spoon-feeding” a hunk of cheese into the mouth of a cool, calm and collected military man from the Alaskan snows with a large firearm firmly balanced behind his bowls. “When guns are hot and time is short, the emergency cheese ration can be eaten as it is—like a candy bar,” carps the copy. “Or it can be mixed with a little water to make a tasty spread for bread. Or the mixture can be set aside for an hour or so and then sliced.” Sliced, spread or diced, America’s fighting men could cool their guns with (purportedly) tasty treats … even during emergencies!

Soldiers, some undressed and others in various stages of uniform, are also featured around a cannon that’s just shot a load in a full-color 1943 ad for Inter Woven Socks. Nothing’s really outlandish here, although a queer eye looking beyond the (presumably) straight soldier guys will probably laugh at the headline: “In Times Like These—Endurance Counts.” While the socks may indeed be “Long Wearing … Comfortable … Good-Looking,” it would be most extraordinary if the battle-weary soldiers were wearing such lovely argyle, striped and solid color socks under their regulation boots and regalia.

Pullman produced several ads in a series illustrated by Albert Dorne during 1944, when their passenger trains carried troops instead of people traveling for pleasure. In one, two soldiers stationed in Egypt are trying to adapt to a particular custom of the country: taking one’s shoes off before entering a home. But until we’re well into reading the copy, we don’t know that. Instead, as a native looks on suspiciously, two GIs guiltily remove their footwear in the threshold of a building. The ad’s headline — “I never did this in daylight before!” — adds to the illicit sense that the soldiers have been caught doing something for which they can be discharged today. “Back home, he came in the house with his shoes in his hand only when he’d stayed out late — to keep from disturbing Mother and Dad,” begins the copy. The implication? Possibly this: He might have been a good boy back home, but now he’s indulging his baser instincts.

A large piece of artillery from a crate of ammo in hand, another shirtless soldier with a somewhat skeptical but determined look approaches a uniformed GI in a jungle somewhere during the war. As he brandishes the burnished shell at his comrade, the headline in an Armstrong Cork company advertisement screams: “Listen, soldier, it just doesn’t make sense!” Is the shirtless soldier menacing the other man, who’s attempting to talk him out of doing something unwarranted or outlandish?

Attempting to gain a sense and semblance of the action here, our eyes wander around the illustration. There’s another soldier smack in the middle, watching what’s going on with obvious delight. Behind him, almost hidden by the trees and foliage, other men stand in front of a cannon or, bare-chested, carry duffle bags above their heads.

Let’s now turn to the advertising copy here and read a conversation between Bill, Joe and Hank. As it turns out, Bill is simply showing the shell to Joe so he can see the Armstrong trademark. Joe, whose father has been selling Armstrong Linoleum in his furniture store, can’t believe the same company manufactures weapons. It’s Hank — the smiling soldier ambling up to them — who explains that the Armstrong companies make a lot of different products.

The graphics and headline of this attention-grabbing ad don’t come across as appropriate for a mild-mannered exposition on the “hundreds of diversified products” made by Armstrong. But that’s how an effective advertisement can work. Shock value grabs our attention as we sort out the pieces, seeking solution(s) to the advertisement’s purpose or message. Appealing to our sense of fear — homophobia … a jungle setting … in the midst of a world war — this homoerotic ad uses language and images to create a complex yet compelling tableau.

Close-knit sailors — perhaps a bit too close for comfort — appear in a 1945 advertisement for Listerine Antiseptic, touted here as “the tested treatment” for infectious dandruff. “Oh, yeah! A month’s pay says it will!” bets the sailor on the right, referring to Listerine’s ability to get rid of the flakes and scales on his buddy’s jumper. Head cocked aggressively with his face uplifted and an expression of bully daring about him, the sailor holds out some money in his left hand while his companion brushes the dandruff off his shoulder. Chastised and chastened, chagrin is etched deeply across the downcast face and furrowed brow of the embarrassed sailor who’s ashamed to look his friend in the eye. Although hardly effeminate, there’s something soft and feminine about the suffering soldier. Here’s a twist, a role reversal from most (non-combat) advertisements of the time that show a man and woman — where she always tends to be the student to him as the teacher. One guy learns an important lesson about personal hygiene from another in this ad. How domestic and degrading for a military man!

Listerine had laid on a lulu of gay ambiguity in an earlier, 1943, ad: By their body language, two bruising sailors appear to be doing some sort of cheerleading or mating minuet as they bend and bow in a bizarre ballet, looking cautiously at each other. “Butch says don’t bring Lulu,” one tells the other in this 1943 ad for Listerine. Leaning close, the sailor seems to be winking wonkshly while his buddy nervously looks around to see if they’ve been caught or observed together. Turns out that little things disturb courageous men like these: “Butch came through a couple of bombings and never batted an eye,” we learn. But when it came to a second date with Lulu, “he wanted out.” Sure, Lulu was a looker – with good “gams, and plenty of oomph.” When shore leave is short, though, a man doesn’t want to spend it with a girl who’s got bad breath. Listerine may have been part of their “passport to popularity,” but our money is still betting on Butch and his flag-waving buddy … leaving Lulu behind.

Epilogue

After the war, titillating ads continued to appear with potentially hidden, coded, or ambiguous gay themes and messages.

“Monogamy at the Naval Academy: Now A Forced-Feeding Social Life,” proclaimed an ad promoting an upcoming story to be published in the March 1, 1958 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. But to what kind of monogamous social life … and whose forced feeding … did the headline allude?

With 1,700 rooms and five miles of corridors, Bancroft Hall — “one of the largest single dormitories in the U.S.” — houses the Naval Academy’s entire brigade of 4,000 midshipmen, states Blaine Taylor (2005) in Military Heritage magazine. Since Annapolis first accepted women as midshipmen in 1976, the purported lack of monogamy and potential erotic overtures among the men housed there tug at the intellect but boggle the mind.

“What will it take for a straight guy to go gay?” asks Kevin Cassell (2004). “Try just a few weeks in the United States Navy during a time when homosexuality was not just grounds for dishonorable discharge, but for a full-scale criminal investigation and, if found guilty, incarceration. Yes, it happened: dozens of young, straight naval recruits ‘went gay,’ with no small degree of enthusiasm, at the Newport Naval Training Station in Rhode Island in 1919.”

Not a well-known fact, shares a friend, but “in the early 1950s, during the height of the Korean War, the military academies were being forced to turn out more officers than they had the capacity to house. Since most of the bunk beds were being shipped out to military barracks, the academies had to resort to double beds in their small rooms, and putting three cadets into a room with two in a double bed. This didn’t last very long when it was found out that the double beds facilitated some ‘buddy activity’ during the night when the bunkmates got familiar with each other. I don’t recall where I first learned this, and I’d certainly go look for a definitive reference before repeating it, but I’m 99% sure it’s true,” he said.

Despite McCarthyism and the myriad struggles predating Stonewall yet ahead, “gay” and homoerotic imagery — explicit or implied — made such headway during the World War II years that the roadblocks to real liberation throughout the advertising world would become fewer and farther between.

But that’s the grist for another article … or, more likely, a series.

Retired communications professor, marketing director, and publisher Bruce H. Joffe has amassed an extensive array of media, management, and human resource experience, along with counseling and “people” skills. Fluent in Spanish and conversant in Portuguese, he has taught public relations, media, marketing, and journalism courses at The American University, George Mason University, Mary Baldwin University, Carthage College, and Kaplan College. The award-winning author of magazine features, academic research, professional journal articles, and newspaper byliners, he has published eight books: titles deal with marketing, the media, interfaith and progressive theology, church reform, gender studies, and international (intercultural) living/communication.